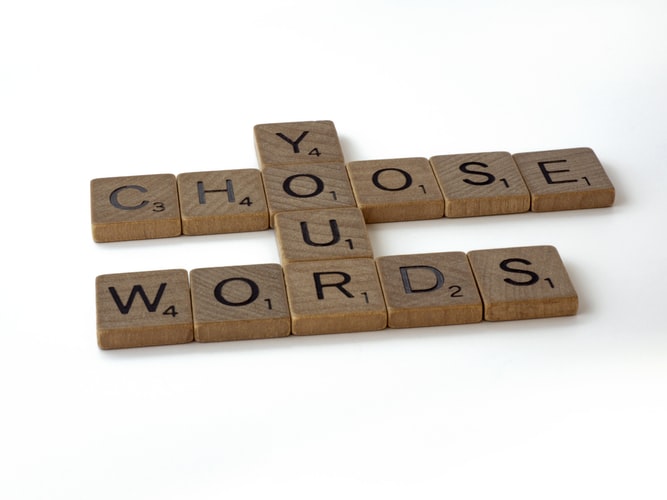

Use the right word. Find the right word

and revise it. Determine the desired meaning, usually from a weak word. Don’t

be lazy about the revised selection. Dig deep into your brain. Don’t just settle

for the first word. Don’t settle for was or blue or table. Don’t be indolent or

lax. Take a moment. Think. Dig. Try a few choices. Roll the choices around in

your brain, on your tongue, in the sentence, in the scene, in the greater

meaning of life.

Think about whether your character would

say it that way, would use that word, would even think that word to describe

his grandmother’s doilies. Let your characters drive you, motivate you to

choose crochet instead of knitted. Use their diction in that tight-third scene

to choose yarn over fiber. Use their experience in that first-person narrative

to choose a better word over your first word.

See it, hear it, smell it as they would.

Express those ideas and thoughts in their voice, in their diction, using their

meaning of the words you choose.

Understand the world you’re creating from

the character’s perspective. Take the time to see the world through their eyes;

take the time to explore the world and the motivations of each character based

on their background and their upbringing. Know that that background and

upbringing is, generally, different from your own. Know that it’s probably very

different from your own background.

Go deeper now, think about a stronger

verb, delete those weak words and reach for stronger words. Write words that

are specific, that engage, that paint pictures through the senses with color

and smell and sound. Evoke feeling through the words you choose, but not

through weak words like think and felt. Evoke feeling through showing with

specifics: gauzy, yellowed-lace curtains sucked out through the window as the

temperature plummets twenty degrees in a few seconds while nickel-sized hail

pelted the battered old house.

Show us don’t tell us. Help the reader

live the experience through specific, special, meaningful words. Let the reader

breath in the frigid, wet air, hike the four-hundred stone steps toward the

peak of the Great Wall, smother in the steamy, over-heated stone sauna.

You see it better now, yes? Choose

Pekinese instead of dog; choose crimson or scarlet or cherry or ruby instead of

red or cerulean or sapphire or indigo instead of blue. Choose shades and tastes

and colors and place names that are specific and evoke deeper meanings not only

for the reader, but for the character experiencing them in your writing.

Write the character from their

perspectives and background and education and thoughts and fears and loves and

hatreds. Writer those characters into settings described based on how they see

their world, or the world they now find themselves in. Take advantage of this

to not only describe the scene, but to more fully develop the character.

Get into their heads and hearts and souls

by choosing meaningful, deep, luscious words that drip with intention.

Do your job with every word you choose.

Choose words one by one that have multiple layers of meaning, words a scholar

or student must pick apart and suck on to gather their full taste and meaning.